Genova - Monte Rosa Ski FKT

On 10 April I accomplished one of my big personal goals for the year: setting a new Fastest Known Time (FKT) on the Genoa-Monte Rosa ski route in Italy. I learned about this route two years ago, when Marcello Ugazio set a new record of 12 hours 19 minutes. My first thought was, that’s insane, but I kept coming back to the idea. A year later, in June 2024, I started toying with the idea of breaking the record myself.

On the surface, it’s obvious why this record was of interest to me. I’ve skied my whole life and also spent close to ten years pursuing elite cycling, so the combination plays to my interests and strengths. But it also resonated with me for other reasons.

First, since I moved to Switzerland four years ago and got back into skiing, my approach to skiing evolved. On one hand, I am now in my late thirties, so the days of hitting rails and dropping cliffs like in my early twenties are well behind me. On the other, snow conditions in Europe are very different from the US, and we just don’t get as many good-snow days. I started gravitating more toward mountaineering and alpinism than chasing the next powder day. As part of this shift, I also started to eschew mechanized travel and mountain huts. Maybe I just like sleeping in a nice bed, but I’d rather wake up at 2 a.m. and start from town than try to incorporate chairlifts and cram into crowded huts.

Where am I going with this? Well, why is the town the most logical place to start a climb? Or the end of the road where you can park a car? It is to some degree arbitrary. We talk about elevation in terms of meters above sea level, so why not start at the sea?

Second, one of my dreams since I was a child was to do a first ascent and/or descent. A lot of people have used phrases like how I “defeated” Ugazio, but that’s not at all how I see it. I think most people look at a sport like alpinism the way they look at a restaurant menu: a set of possibilities. When you go for a hike or want to climb a mountain, the normal thing to do is look up existing trails. I view new speed records and new routes as making the world of alpinism bigger. It’s about making a contribution; showing that something new is still possible. Surely if you put me against the best cyclists or the best ski mountaineers, I will fall short of world class. But I saw this style of record as an opportunity for me to make a contribution to the sport; I see other people pursuing similar records not as people to be defeated but rather as collaborators in expanding the sport.

Approaching these records takes a lot of care and planning. One aspect that I like about it is that you only get one shot (at least per year). The effort itself is so fatiguing that you cannot really train by doing it, and the weather conditions would normally only give you one window in the year when you can try. So you have to train components and try to pull them all together for one big day. I also love the pressure that comes with single day goals. While I find inspiration in projects like The Fifty, I don’t derive as much satisfaction from slowly checking boxes. With a project like trying to set a record or win a particular race, the success of the entire year comes down to just one day.

Maybe some maturity that I’ve gained in my thirties is the ability to know that there will never be a perfect day or perfect preparation. As a cyclist in my twenties, I often thought, if I just make it onto this better team, spend more time training, etc. then I’ll suddenly break through with amazing results. Everybody has problems – even the pros on the biggest budget teams get sick, have interruptions like holiday travel, etc. Successful seasons come from dealing with the challenges, not the absence of them.

In the leadup to this attempt in April, I dislocated my shoulder at the end of March while training in Engelberg. This was rather disconcerting as the record would have me riding a time trial bike for seven hours, and these force your arms tightly in front of you with a lot of stress on the shoulders. You are essentially steering the bike with your elbows, so it requires a lot of fine motor control from the shoulders (in an awkward position already) to control the bike.

My first thought after the injury was that I wanted to push the record until the end of April to give as much time as possible for my shoulder to heal, but around the 2nd or 3rd I saw that the forecast for the following week matched the ideal conditions that I had in mind. One way that attempting a record like this is different from a sanctioned race is that you get to choose the day. The temptation is to always push it later: My injuries will heal, I can do another block of training, maybe the conditions will be even better. But then you will never actually do it.

Despite not managing more than 20 minutes in my time trial position since the injury, I felt that this was the moment. I called up my support crew and asked if they could be there on the 10th. They said yes, and it was set.

We all met in Genoa on the 8th – Christine, Eva, and Claudia flying down from Berlin and Christoph and Rolf driving from Switzerland. William, my ski partner, would meet me directly at the location where I would change from bike to ski.

The first problem presented itself a day early. On the 9th, I went out for a short morning ride to test the final bike configuration. On my way out of the parking lot I heard a snap followed by something rattling on the ground. My headlight. One of the links in the mount broke clean in half. I put it in my pocket and continued on my ride, but internally I was panicking. Most of the bike segment would be on desolate country roads in the night; a working, reliable headlight was critical.

I got back to my van and dumped everything out on the parking garage floor Apollo 13 style, trying to figure out another way to attach this light. I actually had an extra link in Gressoney, a three hour drive each way. Backup plan one: drive there to get it. Six hours in the car is not how I imagined the afternoon before the attempt. Christine offered to go with me. Then I started looking for electronics stores in Genoa. I found one that had GoPro parts on their website. I found some pieces that would work, and with two mounts screwed together plus a bungee cord to provide extra support, I was back in business (although during the record my heart skipped a beat every time I hit a minor bump in the first two hours thinking the light would fall off again).

Go time. We all met in the hotel lobby at 1 a.m. and had a short drive to the beach for a 2 a.m. start. The timing is important.

All the bottles and food prepared.

All the bottles and food prepared.

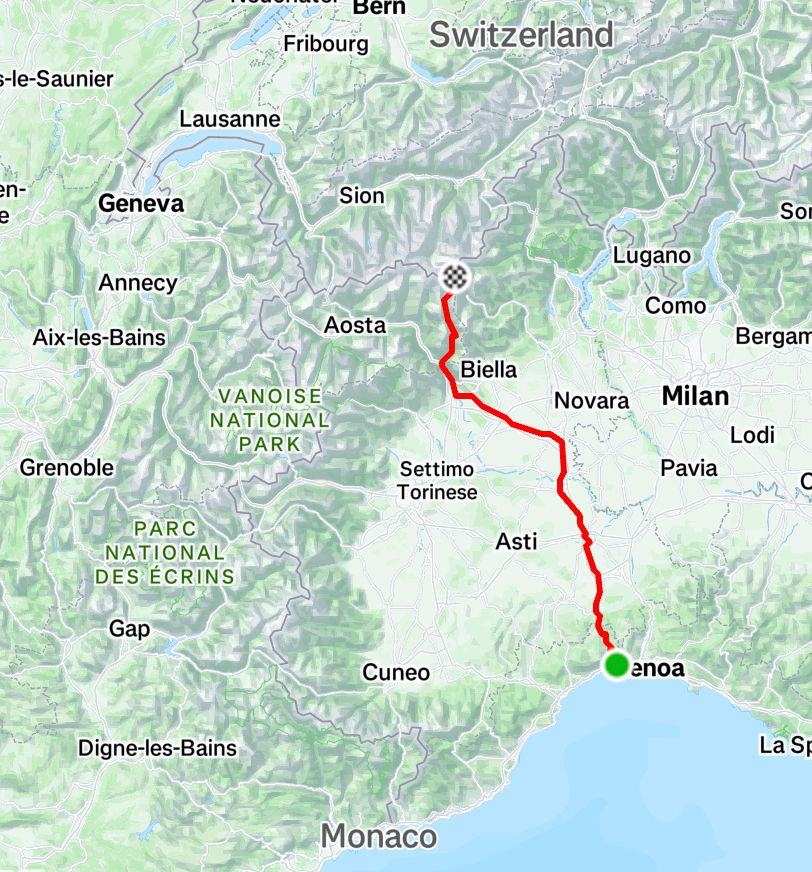

First, a quick lay of the land: The route starts at Voltri Beach and climbs over the Passo del Turchino (about 500 meters). Then you promptly lose all that elevation as you descend down the back to Ovada. From Ovada, you ride a more-or-less straight line over the plains of Piedmont to Ivrea, where you enter the Aosta Valley. This is about the 170 km mark. 20 km farther up the valley you arrive in Pont Saint Martin, where an additional 35 km of climbing awaits. The bike part ends in the village of Orsia after 225 km and at an elevation of 1,750 meters (although with about 2,500 meters of climbing because of ups and downs).

In Orsia you trade the bike for skis. You start climbing in a ski resort until 2,300 m, then turn left and go off-piste. At 3,600 m you pass a mountain hut, Capanna Gnifetti, and go onto a glacier. At 4,240 m you make it to Lysjoch, a pass where you actually descend a little bit and traverse for about one kilometer. It’s also the first place you actually see the summit and Capanna Margherita. From the traverse, it’s a short (on paper) climb to the Margherita, at 4,554 m.

The route from Genoa to Monte Rosa.

The route from Genoa to Monte Rosa.

Back to timing. If you are too early, the piste in the ski resort is basically a sheet of ice, and the climbing skins won’t grip it, forcing you to use crampons and losing the efficiency you get with gliding on skins. If you are too late, there is an awful headwind on the bike as you enter the Aosta valley when the sun comes up and the cold air starts rushing down the valley to replace the rising warm air at the bottom. I saw that Ugazio had started his record at 1 a.m. I made the decision to start an hour later and trade some wind for better ski conditions.

The hardest part of the start is to stay in control of the effort. After a few days of easy workouts and carb loading, plus all the excitement, the temptation is to give it everything off the line. It takes a lot of discipline to keep your eyes on the power meter and just ride the plan. My plan was actually to be a few minutes behind Ugazio over the Passo del Turchino, which I was (by 4 minutes), and then to make it up on the flats.

Me with the bike support team (Claudia and Eva in front, Christine, Christoph, and Rolf behind).

Me with the bike support team (Claudia and Eva in front, Christine, Christoph, and Rolf behind).

Riding into a tunnel on the Passo del Turchino.

Riding into a tunnel on the Passo del Turchino.

I noticed on the descent that it was very cold. I had a wool base layer and some thin gloves, but besides that just a paper-thin skinsuit. My focus was on optimizing aerodynamics, something I thought could be improved from Ugazio. With all my energy and motivation, the air felt a bit crisp but nothing too uncomfortable to warrant a warmer jersey. When I came into Alessandria, around the 75 km mark, I was 5 minutes ahead of Ugazio, having made up 9 minutes from the Turchino. I was also thinking about my shoulder: so far, so good. It was mildly uncomfortable but not painful.

The next major leg of the trip, to Ivrea, is seemingly flat but there are some long stretches with very mild uphill gradients (we’re talking less than 1%). These aren’t so much a physical challenge as a mental one: you cannot let off the power even for a second without slowing down. A funny thing I noticed during this stretch was that the time seemed to pass faster at night than the two times I had ridden this section in training. I think that during the day, when you see endless farmland in front of you, it can feel like you are not making any progress at all. At night, I was just looking at my clock, thinking in 20 minute chunks (the interval at which I was eating). It’s not often that staring at a clock makes time pass faster, but this was one such case.

Riding somewhere in Piedmont.

Riding somewhere in Piedmont.

After passing Ivrea, the sun started to come up, and with it the wind and the traffic. These factors slowed me down a little and by the time I reached Pont Saint Martin, I was back to being on the same time as Ugazio’s record. I admit that this was a little disappointing to me, as I thought that I would be a solid 15-20 minutes faster on the bike. Ugazio is more of a trail runner so I was getting nervous that I wouldn’t have an advantage on skis.

The climb started and the first 3 km are rather steep. I knew right away that I was in trouble. My plan was to ride the final 35 km in the range of 280 - 300 watts, but every time I looked at my power meter it said about 230. My stomach felt fine but when I tried to eat, I hardly had the energy to swallow food.1 Try as I might, I could not hit my target power, and I knew that I was bleeding time.

My support crew had been amazing all day (well, night) with fresh water bottles and energy bars, but it was these next two hours that I leaned on them most. By now, Christine, Eva, and Claudia had driven ahead to the transition point to meet William and set up my skis. Christoph and Rolf were with me on the bike. I pulled over and said I needed a break and was feeling dead. Christoph told me that my ground speed and rhythm looked good, just keep going. But I had ridden this in training and knew that my speed was not fast enough. Mentally, I started dipping into the emergency buffer: I knew that Ugazio spent 24 minutes transitioning from bike to ski and that I had practiced doing it in 10. OK, if I come in late, I can make up the time in the transition, and I just need to ski.

My energy did not get better. There are some flat sections of the climb where in training I was riding 30-35 kph, and now I could barely get above 20. Just bleeding tons of time. I stopped again. Christoph told me that if I just keep moving, I’ll be on Ugazio’s pace. I knew that he was trying to be positive, but also that he was wrong. I had done the calculations and knew the time splits on this climb. But the illusion was enough to get me back on my bike and riding again.

At this point, I had resigned myself to not breaking the record. Even if I came in at the 15 minute buffer, I would have no energy — I could barely even stand up on the side of the road when talking to my support crew. Christoph said, “Hey, remember that what you are trying to do is crazy!” He was right. It’s a big project and my first attempt at a record like this, so it will be OK to fail and learn something from it. And I felt I owed it to my support team to keep trying until the end.

The climb has signs marking each kilometer, but also small placards for each 100 meters. So you see 11.3, 11.4, 11.5, etc. Normally I like the kilometer markers, they are a constant reminder of progress. But on this day I looked at every single 100 meter marker, counting down an agonizing 350 of them.

I stopped again 3 km later to put on a warm jersey and gloves. I really wanted to get in the car. Before I could say anything, Christoph said, “The transition is set up, William is there waiting for you, it’s all ready.” OK, I cannot stop now.

On the climb to Orsia, fully cracked but mountains in sight.

On the climb to Orsia, fully cracked but mountains in sight.

There is a 5 km flat section but then the 5 steepest kilometers at the very end to Orsia. I felt like I was crawling up them, but finally I rounded the last bend and saw everything set up for skis with William sitting on the guardrail with another friend and Claudia, Eva, and Christine jumping and cheering. The clock was at 7 hours 22 minutes and I was 22 minutes behind Ugazio’s record and had no energy left.2

The transition was set up perfectly. I hardly sat down on the tailgate of the van when I had an energy bar in one hand and a can of Coke in the other and Christoph was taking my shoes off. My plan was to eat and drink a lot during this “break” but I only managed half the bar and a little bit of Coke and water. Nonetheless, I was walking away from the van, skis in hand, in only 9 minutes.

Everyone helping out while changing to skis.

Everyone helping out while changing to skis.

Then the magic happened.

The skis were on and I was skinning up the piste with William and his friend Cristiforo. It felt like a whole new day, like I hadn’t just spent over seven hours on a bike. We were talking, I was breathing through my nose, and I checked my watch to see how fast we were going: climbing 1,240 meters per hour! My goal pace was to stay around 800-900. Suddenly it was back on. I thought that maybe there is some hope left.

Suddenly feeling good again at the start of the climb on skis.

Suddenly feeling good again at the start of the climb on skis.

Just a cool picture that Eva took while they were waiting.

Just a cool picture that Eva took while they were waiting.

From the piste to Orestes Hut there are a few kilometers with hardly any elevation gain. Kick, glide, kick, glide, try to keep a rhythm. After Orestes you climb a short couloir. I had trained this with crampons on so I reflexively started taking them out of my pack. “Joe! What are you doing? No crampons, just walk!” William said. And he was right, it was a little later in the day than I had trained and the snow was soft enough to walk without crampons.

Once back on skis and moving again I started to feel the fatigue come back. “Come on Joe, halfway there,” William said. I saw that he was right (again), 1,400 meters climbed since the transition, 1,400 to go. The climb is very steady all the way to Lysjoch. Sometimes I set the pace, sometimes I followed William. Just keep moving. I wanted to stop for breaks but William always told me (and sometimes quite colorfully) to keep going.

When I passed Capanna Gnifetti I checked my watch: 10 hours 15 minutes. And I knew I was going to make it. 1,000 meters left to climb in two hours, I can do that in my sleep. The only thing that could stop me was if I stopped; just keep moving, no matter how slow.

Entering the glacier just after passing Capanna Gnifetti. Only 1,000 meters left to climb from this

point, but you still cannot see the summit.

Entering the glacier just after passing Capanna Gnifetti. Only 1,000 meters left to climb from this

point, but you still cannot see the summit.

A brief interruption / commentary here: I cringe at the soap operification of sport, like when a reporter asks a race winner what they were thinking when they crossed the line, and they have some story like, “I was thinking of my grandfather.” I’m sure it’s true sometimes. I didn’t win many bike races, but when I did I was usually feeling like the king of the world that day. Sometimes a bike race is just a bike race, and I don’t think there’s any shame in feeling good about winning one. Anyway, seeing that I was back in business to set a new record, I was really thinking of my support crew while I climbed these last 1,000 meters. I had lost all hope on the bike and wanted more than anything to just get in the car and give up. Everyone there kept me moving along and I just didn’t feel like I could stop at any point. If I were solo, I would not have even put my skis on.

The conditions on the glacier were absolutely perfect. There was a solid track from other climbers the last few days and there wasn’t even any loose snow blown on top of it.

The 600 meter climb from Gnifetti to Lysjoch felt like it took forever, but in hindsight it’s a blur. For so long I was just thinking about the short respite I’d get on the traverse. Finally I made it and caught the first glimpse of the summit.

After the traverse, there is about 300 meters to climb on skis and you can see the destination the entire way. Normally 300 meters is nothing to me but this time it was horrendously slow. I kept checking my watch thinking that my eyes must be lying to me; the destination must be closer than it looks. But no, when I felt like I had climbed 50 meters my watch said only 20. This was rather discouraging and I wanted to stop, take a break, collect myself – but no, I could see the end, just keep moving.

The view of the summit and final pitch.

The view of the summit and final pitch.

The final 50 m of elevation needs to be climbed with crampons. I popped the skis off and put my crampons on, and was off on foot. Head down, I counted 20 steps, then looked up to see my progress. Repeat. Again, again, again. But finally the finish was right in front of me.

I walked across the ridge to the observation deck of the Capanna Margherita and stopped my watch at 11 hours 52 minutes 09 seconds. This was 27 minutes faster than the old record, meaning I had somehow found the energy (and good conditions) to do the ski ascent 34 minutes faster.

Then I sat down on the floor. There was already a group of climbers there and one asked me, “Where did you start this morning?”

“Genova”, I said.

They briefly looked at each other like maybe I didn’t understand the question. Then he said, “That’s insane.”

The summit, clock stopped, can relax.

The summit, clock stopped, can relax.

Celebration photo with William.

Celebration photo with William.

Everyone together back at the road after skiing down (Eva, Angie, Christine, Claudia, Christoph,

me, Rolf, William). (Cristiforo took the lift to go back to Alagna.)

Everyone together back at the road after skiing down (Eva, Angie, Christine, Claudia, Christoph,

me, Rolf, William). (Cristiforo took the lift to go back to Alagna.)

A Few More Shoutouts

- The whole support crew on the day: Christine, Eva, Claudia, Christoph, Rolf, William, and Cristiforo

- Eric Balog, for tons of discussion about strategy / gear / optimizations

- Martin Zhor, for collaborating on preparation and putting up with me 🙂

- Angie Dalton, for connecting me with Eva and Claudia and general encouragement

- My employer, Parity Technologies, for remote-first work, general flexibility, and lots of support in being able to travel / train

Footnotes

-

Just preparing the food the day prior is an effort in and of itself (shoutout to Christine for helping). All together, we mixed 10 liters of energy drink and divided it into bottles, Nalgenes (for refilling the bottles), and soft flasks (for skiing). Then we put 28 energy gels (I really wish they sold bulk bottles instead of single-serve packets!) into more soft flasks as at that amount they are easier to eat from a flask compared to opening each one on the go. Then we divided them into buckets (one for each car plus one for my ski backpack). On top of that we had about 10 energy bars and some other single-serve gels of different flavors just to mix it up from what was in the flasks. And a few cans of Coke for the transition. Oh, and I ate pretty much everything during the effort. ↩︎

-

Looking back on the ride a few days later and the meltdown on the bike, I think the cold temperatures in Piedmont sapped a lot of my energy. I was too focused on the effort to feel cold and I didn’t want to put on a less aerodynamic jersey. But Christoph told me that when I asked for it on the climb, that phase was actually warmer than a lot of the time earlier in the night when I didn’t want the jersey ↩︎